Dialogue System

Conan, What is Best in Programming?

There’s an adage among computer programmers that goes like this:

“The best code is the code you don’t have to write.”

I don’t know who first coined it, but if you look around you’ll find no shortage of clever nerds (myself included) repeating this mantra in its many permutations. I’ll give you a few more famous examples just because I can:

“Measuring programming progress by lines of code is like measuring aircraft building progress by weight.” - Bill Gates

“Every time you write new code, you should do so reluctantly, under duress, because you completely exhausted all your other options.” - Jeff Atwood

“If we wish to count lines of code, we should not regard them as ‘lines produced’ but as ‘lines spent.’” - Edsger Dijkstra

Is the horse dead yet? No? OK one more ought to put that smelly horse in the ground.

“Perfection is achieved, not when there is nothing more to add, but when there is nothing left to take away.” - Antoine de Saint-Exupery

You may be wondering why I’m telling you this. That’s good! It’s good to be curious! In this post, I thought I’d share some slightly more technical details about some of the software decisions made during the development of Voodoo Detective. It’s a big topic, so I’ll only be focusing on our dialogue system for now.

Whether you’ve been here before or this is your first time, welcome to the blog! I’m so happy you’re here! Please feel free to check out my last post where I talk about character design.

Unity

Before I get too far along, it’s important for me to explain that Voodoo Detective is built using a real-time development platform (AKA Game Engine) called Unity. Unity is free for indie developers to use until their budget or revenue exceeds $100,000 at which point it costs $40 per month per developer for the duration of the game’s development. They have a wonderful array of documentation, tutorials, a thriving developer community, and a huge library of free and paid pre-made assets you can use in your own game.

When you develop a game for Unity, you’re most likely using a programming language called C# developed by Microsoft.

Oh What a Fool am I

While all those wonderful quotes from earlier are hopefully still fresh in your mind, I’ll spoil the denouement by saying that when I began working on the dialogue system, I foolishly disregarded those wise words and attempted to write my own system from scratch.

I was too eager to get started and could have saved myself a lot of pain by carefully listing out my requirements and then looking around to see if any software already existed that could satisfy those requirements (spoilers: it does!). Instead, I elected to jump right in with no real plan or understanding of the complexity involved. Shame on me! I should know better by now.

*author pauses to slap himself*

I will say that I learned A LOT about Unity in the process so it wasn’t a complete waste of time.

Movies versus Games

The tricky thing about game dialogue that you don’t have to worry about when you’re writing a script for television or film is branching dialogue that changes based on the viewer’s decisions.

For instance, if you’re watching Cyrano de Bergerac (I recommend the version with José Ferrer), as the viewer you don’t get to pause the movie and force Cyrano to tell Roxane that he loves her. You have to endure his insufferable nobility all the way to the end of the film.

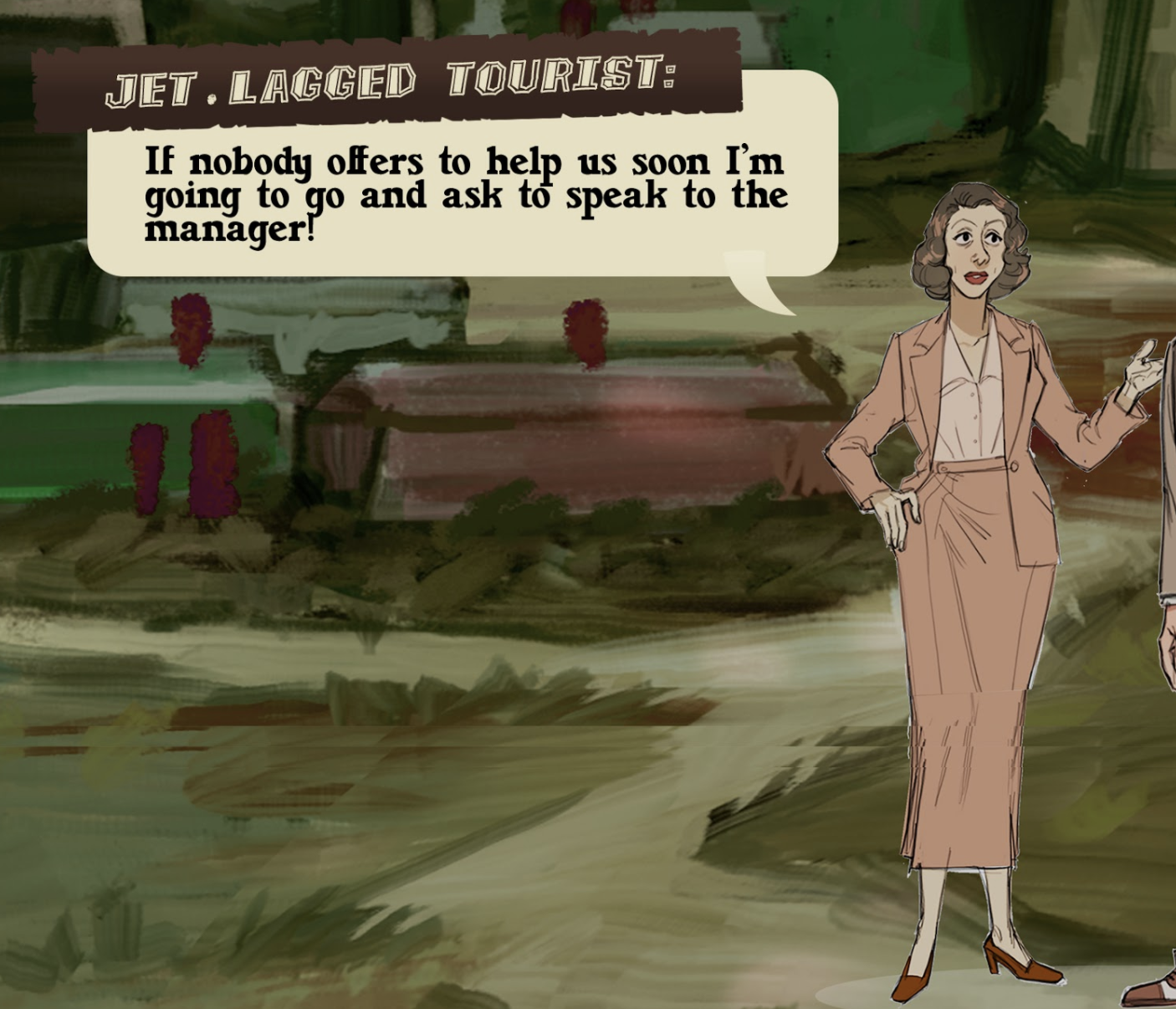

In Voodoo Detective, the dialogue for the game is broken up into “trees” with many “branches.” You may start by saying, “hello,” but where you go from there is dependent upon what the player is currently investigating.

Here’s an example:

Voodoo Detective: Hey, Ricky.

Ricky Tinsel: Hey VD, what can I do for you?

Options

Option 1: I need to know more about Gordon Crumbsford.

Option 2: Pour me a drink Ricky, and make it stiff.

Option 3: Actually, I’ve gotta hit the bricks.

One thing games do have in common with film is that whatever dialogue you have will need to be recited, over time, by actors, within the parameters of the blocking laid out by a director. In a game, that’s all done with code so we have to have a way to instruct the computer when a line of dialogue should be recited, which actor needs to recite it, and how a scene should be blocked out during the recitation.

So this is where the post briefly gets a little more technical.

In computer science, it is very common to model data (such as our dialogue trees) using graphs. A graph is a set of “nodes” connected together by “edges.” Check out this sweet graph.

I decided to store our dialogue trees as graphs using a file format called YAML (a recursive acronym - YAML Ain't Markup Language). Here’s an example of how that looked.

I realize now, that this is going to be very hard to understand for anyone unaccustomed to reading YAML, but basically the numbers in bold indicate time and everything sectioned beneath those numbers represents everything that happens at that moment in time during a conversation.

So in my dialogue system, I was calling conversations “sequences,” but to return to the “nodes” and “edges” terminology for graphs, each “sequence” represents a single “node” and within the sequence, “edges” are represented by “!Sequences.LoadSequence.” This particular sequence is called “vd uses himself.” This would have been the sequence that takes place when you click on Voodoo Detective. He would say something like, “I look pretty good in my trench coat.”

I won’t go into any further detail here because to really explain what’s going on would require a little more computer science background than will fit in one blog post.

Unity Timeline

I had my conversations modeled as graphs, and stored as YAML. I had written software capable of loading the YAML files and then executing the instructions therein in order to play conversations (“sequences”) in the game.

This turned out to be an extremely unwieldy solution. In case you hadn’t noticed, those YAML files aren’t entirely convenient to read (or edit). You can’t really tell at a glance what’s going on in a conversation and any changes you make to the timeline force you to rearrange the rest of the timeline manually. It’s an ugly solution and I don’t know what I was thinking.

I decided to throw all that trash away, and try to make use of a facility built-in to Unity called Timeline. I don’t know if this will mean anything to you but, Unity’s Timeline feature is very much akin to film editing software. You’re given a timeline you can place different “tracks” on. “Tracks” represent sounds, animations, and anything else in the scene you could possibly want to manipulate.

Here’s a video tutorial on how to use Unity timeline. In the scene he’s working on, you can see he’s trying to turn the tank’s turret, play the sound of an engine starting, point the camera at a car, and then show that car moving towards the tank. At the bottom of the screen, you can see the timeline scrubbing over the camera, sound, and vehicle tracks.

So I went about trying to model my dialogue graphs using a simplified version of my YAML file from before. I’ll spare you the details, but this time instead of representing the timeline with numbers, I reference a Unity Timeline instead.

This solution was a good deal cleaner, and allowed me to test the scenes without playing the game, but it was still pretty ugly because as it turns out, it’s can be a big pain in the butt to try to extend the functionality of Unity Timelines beyond the explicit use cases laid out by the Unity Timeline developers.

Put Down the Keyboard

I was still pretty unhappy with the dialogue system so I decided to step back, and do what I should have done from the beginning: enumerate my requirements and see if there already existed any software to satisfy those requirements.

Here was my list of requirements:

Store dialogue graphs

Handle save game state (allow for modification via scripting language)

Inventory State

Game Progress State

Actor Database

Item Database

Conversation Database

Graphic user interface for conversation graph management

Allow for blocking and complex scene management

Display text and play audio for conversations

Handle localization (i.e. store multiple translations for text in the game)

After writing this out, I realized I could program a dialogue system to handle all of this, but that it would be a significant undertaking. So finally, I looked on the Unity asset store and found something kind of amazing. It’s called Dialogue System for Unity.

In exchange for $85, I could save myself weeks (maybe months) of development effort and instead instantly have access to an actively-supported, fully-baked, battle-tested dialogue system. I think it’s the best $85 I’ve spent in my entire professional career. Here’s a little snapshot of the dialogue editor UI.

Lesson learned! You mustn’t only repeat the wise words, you must heed them too!

Ready for the Weekend

I don’t know about you, but I’m ready to start my weekend! Thank you all so much for reading this mess. I hope you have a delightful and relaxing weekend. Now let’s never talk about dialogue systems ever again.

Love,

Eric Fulton